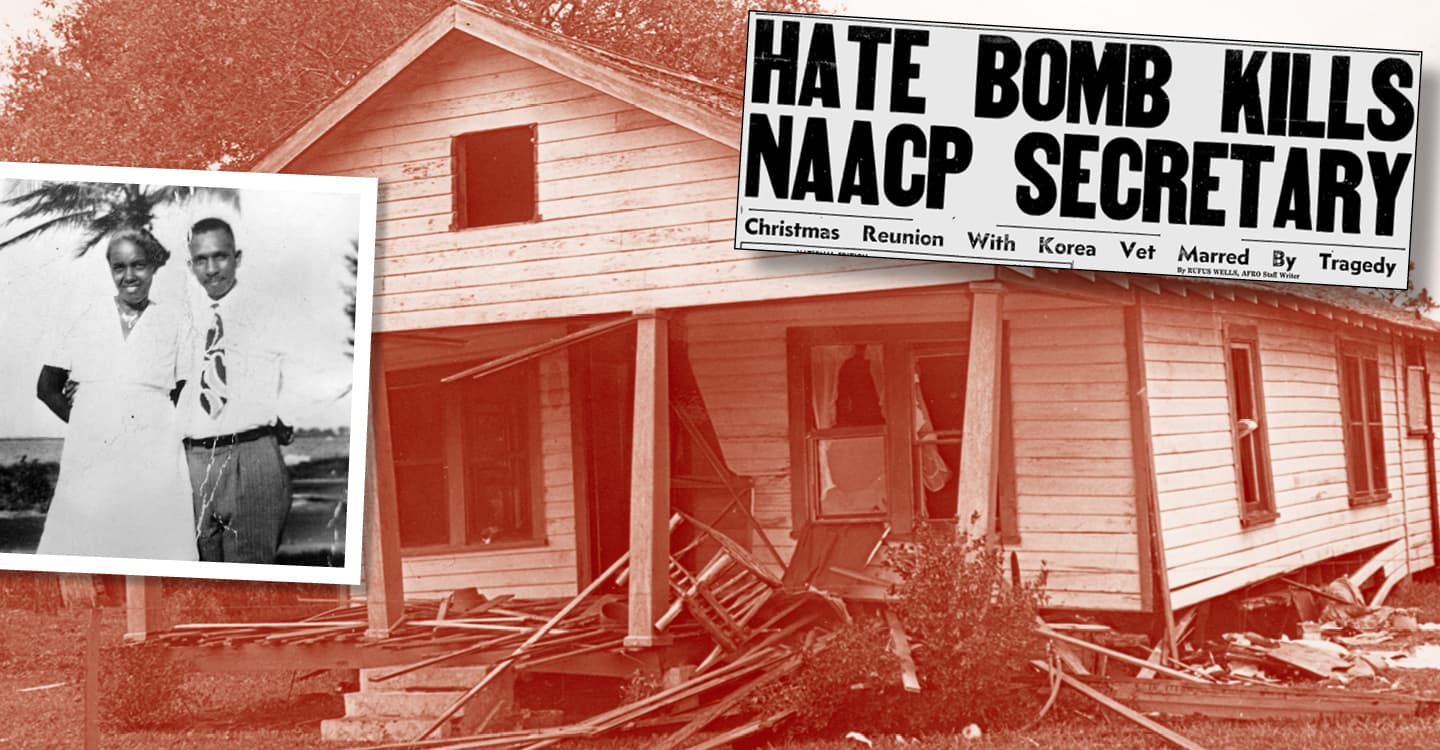

December 25, 1961 was a day of celebration for Harry T. Moore and his wife, Harriette. Not only was it Christmas, it was their 25th wedding anniversary. But the festivities turned tragic that night, when a bomb hidden under their house in Brevard County, Florida, exploded, killing the Moores.

Members of the Ku Klux Klan (K.K.K.) were suspected of carrying out the attack as retaliation for Harry’s work fighting for equal rights for African Americans. As the founder of the Brevard County branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Harry had helped register African Americans to vote, fought for equal pay for black teachers, and worked to expose lynchings of African Americans in the South.

But no one was ever charged with the murder, and the case remains unsolved to this day.

That killing is one of 128 unsolved murders from the civil rights era that have been reinvestigated in recent years by the Justice Department. But most of the suspects in these killings are now dead and can’t be prosecuted—as are many of the witnesses—leading the F.B.I. to mark most of these cold cases “closed.” That makes it difficult for the victims’ relatives to gain access to the case files and find out what happened.

Now that may change—thanks to a group of dedicated high school students and their teacher. The A.P. government and politics classes at Hightstown High School in New Jersey recently drafted and lobbied for a bill that requires the files of civil rights-era cold cases to be collected and released to the public. The Civil Rights Cold Case Records Collection Act passed both chambers of Congress last December, and President Trump signed it into law the following month. It’s believed to be the first time a high school class has drafted and gotten a federal law passed.